Va Va Voom | |

| Va va voom! Biff bang pow! Certain phrases lend themselves to repeated reflection. Those phrases contain the rough essence of the magic of big band sounds at their most impulsive. Woody Herman, for instance. The mid-40's incarnation of his band The Thundering Herd gave it their all repeatedly and without reservation. I love the pioneering ramshackle sounds of 'Four Brothers', later given the stomping with a feather boa treatment by Anita O'Day. Here the front line of young tenor saxist Stan Getz and the baritone sax of the inimitable Serge Chaloff combine winningly, the tune crisply pressed and elegantly executed. Or 'Your Father's Moustache', with the golden vibes of Red Norvo playing alongside ace marksmen like the Candoli brothers, and future arranger for the Batman TV series Neal Hefti. Who could put a candle to such feats of zigzagging insinuation? I'm reminded of the Greek garage mechanic in Aldrich's Kiss Me Deadly, the sole friend of lone tiger Mike Hammer, whose catch-phrases included 'pow!', 'my father's moustache' and 'va va voom'. Herman's herds trample over standards of musical decency, demonstrating instead the kind of duende which wins Spanish bull-fighters the ultimate plaudit- the tail, hoof and ears of the vanquished bull. |

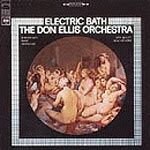

| Similarly, I can't listen to the recorded output of trumpeter Don Ellis without pondering how much energy was concentrated into his most electric performances. The head of steam he generates with his band on 'Turkish Bath' is worthy of the title, the feeling of languor amid blow-torch concentration of heat and incandescent vapour. Ellis's idea of a Turkish bath is slightly more challenging than a friendly social gathering or classical vision of naked bodies brought together in communal revelry, as suggested by the Electric Bath lp cover. It calls to mind the scenes of blistering intensity which regularly spring to life in the Westerns and films noirs of the great Anthony Mann. In the wonderful T Men a lead character is bumped off by being trapped in a sauna as the temperature is cranked up beyond human endurance. In Ellis's case hyper-kinetic is less a description than a way of life, playing for keeps with every spare second at his disposal, putting together hand grenade trumpet solos in fearsomely complex time signatures. As for his orchestra of bongo, sitar, clavinet and other otherworldly shaven-headed warriors, their musical energies provided the fuse which regularly lit their leader's explosive tours de force. 'Open Beauty' from the same album shows Ellis in eerie reflective mode. The sound-world here is closer to Broadcast of Work and Non-Work vintage. Droplets of spooky keyboards merge with a pastoral flute to form a spacey, blue-eyed purity. This is music which conjures up those extreme moments of anticipation and acceleration, only to contrast it with the most seductive come-downs. A track like 'Whiplash' provides exactly that, a trumpet-driven headlong rush through the chicanes and Ascari bends of a circuit like Monza. Imagine Steve McQueen on his motorbike, Ryan O'Neal with his fabulous late 70's open shirt collars pulling off insane feats of law-defying power steering in The Driver, with Isabelle Adjani. Then take the bongos and basses which assemble in unison at the start of '33 222 1222', from Ellis's Live at Monterey set. The title could be a phone number or one of his brain-scramblingly complex time rhythms, a wartime code asking to be cracked or a particularly pinpoint set of navigation instructions. The bowed basses grind together in a way Sonic Youth and Roswell Rudd would applaud, rubbing together to generate the friction necessary for take-off. It's a shame Rudd wasn't part of Ellis's set-up, their similarly attuned eclectic mind-sets would have meshed formidably were it not for Ellis's untimely demise. The opening has the same kind of growling primeval lurch present in Rudd's cover of Jennifer Jason Leigh's glorious cover of Costello's 'Almost Blue' in the film Georgia, that is to say harsh and heartfelt in equal measure. This is Ellis's music. There's not a trace of smugness or inertia to bring things down to a prosaic level. |

| While Ellis borrows from the great tradition of orchestral writing in jazz, the Ellington band of the 40's driven mercilessly along by Jimmy Blanton's bass lynch-pin let's say, there is individuality and a sense of adventure here which comes up fresh at every listen. Just listen to the way he uses Dave Mackay's organ on the live album, more akin to the slashing Zorro-like foraging of The Rascals or the swirling Hammond drive of Milt Buckner. There's a ferocious glare to the Buckner style, all locked jaw and bristling forearm jabs. In his shadow, Jimmy Smith is exposed for the charlatan transparencies he was wont to dispense on countless Blue Note dates. If Jimmy Smith was the Cat, Milton Buckner was the Panther of their chosen instrument. Buckner at his best possesses the slow-burning intensity of Victor Buono in cigar-chomping, sprawling intimidation mode. Spewing out threats to Bette Davis in the Grand Guignol Hush Hush Sweet Charlotte, he was the kind of actor who makes twisting a doll's neck out of shape a thing of ghastly portent. The fact that Eldridge Cleaver recounts the anecdote of hearing about the assassination of Malcolm X in prison after seeing a screening of The Strangler with Buono is relevant enough. A mind as fine-tuned as Cleaver's was during the writing of Soul on Ice wouldn't have missed the irony of using the prison's choice of entertainment as background to project his loathing of the white man's cultural perniciousness. Highlighting Buono the moustachioed Italian-American's role as the twisted killer, it suggests how he could become a voodoo doll for Cleaver, a cry-baby impotent Brando. Similar sounds which are called to mind are the slowly ticking time-bomb theme music by the great Henry Mancini for Touch of Evil, or Lalo Schifrin's fantastic collision between helicopter blades and his Latin rhythms on the pulsating soundtrack of Don Siegel's Charley Varrick. The motto 'Last of the Independents' which earmarks Walter Matthau in that film is just as relevant to our man with the four-valved horn- touchingly, the live Monterey recording is interrupted by an aircraft roaring by. Also bongo-led and beautifully put together is a Brazilian lp called Meu Balanco by Waltel Branco, reissued on the Mr Bongo label, curiously enough. Short snippets of street-slick muscle-tightening music, utterly unfazed by fear of embarrassment at wearing its heart on its sleeve so eloquently. Branco might be a shadowy figure alongside the likes of Jobim or Marcos Valle, but he has a great ear for detail and melody, as opposed to the Charles Ives-like rigours of Ellis say. This is superbly visual music. A track like 'Walking', which is slow and stately, reminds you of that thrill of reaching a pedestrian crossing and being greeted by the flashing green man- walk, don't drive. At other times the intensity generated by the band is irresistible, monumental beats whipping up a storm worthy of David Axelrod. |

| As an aside, it's also feasible that any track on the Branco lp could be used as a TV show theme tune, a cop show along the lines of Starsky and Hutch or Miami Vice, but with sharper clothes and infinitely more enigmatic dialogue. It reminds me of how Kevin Rowland came up with a theme song used during prime time viewing, or of Lawrence coming up with a version of the 1970's Robin's Nest Theme on Novelty Rock. While aboard the runaway Lawrence freight train, how many of the Pulp fans who bought Denim on Ice could zero in on the Eldridge Cleaver reference? |

| And what of Go-Kart Mozart? It proves he can still come up with conclusive evidence of his genius, in between the deliberately throwaway camouflage. Synthesized candyfloss noodling will wrong-foot the masses, if they had ever expressed an interest in Birmingham's finest export. 'Selfish and Lazy and Greedy', an anthem for anathema- 'I tell ya losing limbs on the night shift track- Blagging compensation for a dodgy back'. With a cover that pictures the strangely appropriately named Bull Ring Shopping Center in Birmingham, Lawrence shows he can pull off the most daring raid on this listener's sympathy. It's a ragbag of mock-turtle melodies and sneering bile, but there's beauty in there and the vulnerability of those candles in a church moments Felt weren't afraid of confessing to. Like Roswell Rudd embracing the gawky, spikily off the rails beauty of Jennifer Jason Leigh on his Broad Strokes album, Lawrence steps in to stake his claim on the quixotic vamp Wendy James: 'Elvis C you shouldn't have written her solo elpee- It should have been me'. The references to Genet in 'Sailor Boy' would be labelled crude in other hands, but it's a perverse and fitting tribute. 'I'm a sailor boy- In a Rotterdam cell Genet and me get on well...' begins the story. Genet the awkward rebel, doing time in prison, Saint Genet the clumsy shoplifter, inspiring any number of mavericks, fighting for the most wayward causes. Genet the imp of the underworld, a bourgeois in wolf's clothing, a white Black Panther with a fondness for the PLO. Genet the undisputed bad boy of French literature, throwing a gloriously tarnished vision of social mores back in the face of his contemporaries. Lawrence can put petty crime into a song with the same unflinching candidness as The Slits' 'Shoplifting' on Cut. I'm glad to find Al Alvarez's The Savage God, his study of Sylvia Plath, suicide and other short stories, namedropped on his reading list. Whatever else has been dropped from Lawrence's world over the last decade, it's plain to see he's still drawing on those precious moments of flight and survival, the last dance, the last poem, the finality without which new beginnings aren't possible. For the last time, pop music rearing up from the canvas, swirling clouds of digital keyboard, a hyperkinetic scramble to the next carriage before the train derails. Accident! Fire! Theft! Monuments to risk, with no safety net or insurance policy. Those moments threaten to run away from pop music for good. © Marino Guida 2001 |