Why there's no mention of Kent records in the records of Kent

| |

| Alan Warner's Morvern

Callar is a curious book. I am not sure how much I liked it. There's a lot of music in it though. You would expect that from a book dedicated to Holger Czukay and Peter Brotzmann. At one point, Morvern puts together a sunshine compilation cassette, which is something I always do too. On Morvern's tape there is a James Chance track. On my own summer soundtrack, there is a bit of James Chance too. And other blasts of New York No Wave and Mutant Disco from the fabulous forthcoming Ze compilations. And some Glenn Branca too from the reissued 99 Records set Ascension. Otherwise, besides some of the brilliant Broadcast Pendulum EP, it's very much a selection of old soul and UK folk explorations, like Shirley Collins, C.O.B, the Johnstons, Barry Dransfield, Sweeney's Men, Mr Fox, and the like. Nothing too startling I'm afraid, and of course salvage experts with more money or time than me have kindly left the signposts.

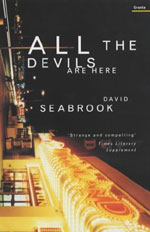

The really curious thing about David Seabrook's book All The Devils Are Here is that music hardly features at all. It's a book about Kent. It's a post-Iain Sinclair book about Kent, and I'm not sure how much I liked it. I think there will be quite a few post-Iain Sinclair books soon about different parts of the country. Just as post Nick Hornby there were quite a few books about blokes growing up with football and music. A good example of the latter being John Kelly's Sophisticated Boom Boom, which is a lovely light read about growing up in Enniskillen in the late ï70s/early ï80s where nothing seems to happen. It almost made me want to hear Thin Lizzy again, and there are enough of the 'right' kind of musical references to make Mojo froth at the mouth. Actually that's a little harsh as, we have said before, the great Lois Wilson does a grand job there keeping Kent Records' salvage operations in the public arena. Anyway, All The Devils Are Here is a book about Kent which doesn't mention Kent Records, or even Billy Childish and the Medway swamp rock scene. As the author sets great store by mentioning his original Crombie a few times, it's surprising he doesn't mention at least the Prisoners when he writes about Rochester and Chatham. I rather like the fact he has avoided all that lot actually. Seabrook adopts the Sinclair trick of using a visit to a place, to shoot off at all sorts of tangents, and collect up a few interesting tales and strange obsessions to stir our curiosity and set us off exploring. So, Seabrook's Kent has nothing to do with the Channel Tunnel Rail Link, Peasant's Revolts, Bluewater and converted oast houses. Instead it's a grainy Morrissey world of haunted writers and fascist sympathisers, fallen Carry On stars and shadowy boxers, sociopaths and psychopaths, asylum seekers and resorts on their last legs. It's a good read, and Seabrook makes some good connections. Occasionally you wish he would go further. Anyone who knows Broadstairs and the 39 Steps would want to mention the 78 steps at the Sandell Street entrance to Waterloo East. It's irresistible. |

| I am a big Iain Sinclair

fan by the way, but not of his fiction. Along with, say, Shena Mackay and

Bill Drummond, he has one of the best minds of his times. His world is not

mine, but London is lucky to have him as its psycho-geographer-in-residence.

He's rightly caught the public's imagination, but you sense he would be wandering

and scribbling, researching and mythologising regardless. Across my room I can see copies of Sinclair works, Liquid River and Lights Out For The Territory. I love the way he describes Lights Out as a collection of speculative essays. I have a copy of London Orbital here too, and I relish the idea of reading it sometime soon. I deliberately haven't read it yet. I'm scared that it might distract me, influence me, or simply make me give up in shame at being a bit of a dabbler and dilettante. I know I lack the discipline and drive to be in the Iain Sinclair class. I know I am too much into pop music and punk rock, so would only fill any psycho-geographical jaunt with obscure and obvious pop references. There's not that much music in Sinclair's writing either. Mind you, one of the best things of his I have read is the new introduction to Alexander Baron's The Lowlife, one of the great London novels. There Sinclair mentions that in the mid ï70s a speedfreak mate of Malcolm McLaren's points him in the direction of The Lowlife. Even better the introduction starts: 'We live at a time when the pre-forgotten seek out the reforgotten, the old ones, hoping to verify a mythical past.' In the Harvill Press London Fiction Series that The Lowlife resurfaced in, one of the other titles is Maureen Duffy's Capital, where the main character Meepers predicts Sinclair in mapping the city, and hearing beneath its surface the urgent whispers of the past, convinced they are predicting London's future. Like Sinclair, it shoots off at tangents, with lots of historical diversions. In this introduction, it is noted that 'Duffy knows, too, that the vast majority of the vanished have no statues or monuments or a page or footnote in a history book to celebrate or denigrate their existence.' Which is why we need people like Sinclair and those that tread in his footsteps to rediscover and reinvent the traces and tales, and leave signposts and suggestions. Even if they are not ones we particularly want to stumble across! © 2003 John Carney |