The Graphic Novel gets Graphic.

Chris Staros at Top Shelf has said repeatedly that Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie’s The Lost Girls is, by a significant margin, the most important book that his imprint has published. This is some statement, particularly given that Top Shelf was responsible in 2003 for publishing Craig Thompson’s Blankets, a book that I personally regard as one of the defining moments in the development of the graphic novel. But Staros is nevertheless correct in his comments, not least because Thompson is not (or at least is not yet) the legendary comics figure that Moore is. From the most easily recognisable spandex clad superheroes, through Hollywood adaptations of Jack The Ripper conspiracy theories, it is fair to say that, where comics are concerned, Moore has seen it all. It’s also fair to say that, as an industry, he’s found it somewhat lacking. This is surely part of the reason that he has turned his back on the shiny glass towers of DC-land and has instead pitched in with the Indies. Well, perhaps that and the fact that The Lost Girls is set to be one of the most controversial topics in the comics world for quite some time.

For Alan Moore has been very clear in his assertion that The Lost Girls be defined as pornography. Your personal context will naturally determine exactly how you respond to such a claim, just as it will determine how you would to the book itself. Me? I’m torn somewhere between the tension of typical middle class liberal guilt and outrage, and writing it off as a tacky attempt to score some scandal points to help generate publicity.

But if this is pornography, as Moore insists it is, then it is a pornography that is at once both heroically new and historically old in the same breath. That is, if notions of old and new are relevant at all since the triumph of Post-Modernism. Indeed, Moore has always been a master of taking the historical document and re-inventing, or at least re-integrating it into a contemporary artefact. His League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen collections do it with rare aplomb, weaving as they do a myriad of threads from late Victorian / Edwardian periods into both contextual treats and ripping adventures. They are both extraordinarily effective entertainments and rampantly complex webs of reference, as evidenced by Jess Nevin’s exhaustive accompaniments Heroes and Monsters and A Blazing World (both Titan Books). Even the mammoth Jack The Ripper classic From Hell (recently reprinted by Top Shelf) which he created with Eddie Campbell has moments where the fabric of time tears, allowing a modern world to peek through: a thoroughly fitting nod to the notion that the mediated hysteria surrounding The Ripper could well be seen as being a defining moment in the historical journey from the Industrial era to the birth of Modernism.

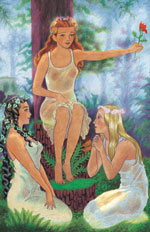

Much of Moore’s finest work could be seen as striving to make connections between the past and the present. With The Lost Girls Moore again plays the literary magpie game, plucking players from other creators’ pasts (the central characters are Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz, Lewis Carroll’s Alice and Wendy from Peter Pan) and bringing them together in a new imaginary context that will no doubt cause more than a little consternation from those who feel such things should not be tampered with. Particularly when it concerns those characters having, ahem, ‘experiences’. Certainly there are concerns from Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children (who own the UK rights to all Peter Pan characters), which means that for the time being at least, The Lost Girls will only be available in the UK on import.

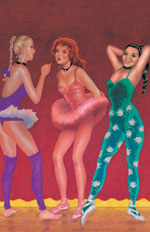

Now it might be argued that pornography itself is as old as history. Certainly it could be said that the advent of industrialisation and the media juggernaut unleashed by the Modern era might be responsible for the development of the popular definition of pornography which we largely ascribe to today. Which is to say, an implicit pornography that increasingly pervades the fabric of our society; a society where contestants on primetime television shows proclaim their hopes of finding employment in the porn industry, and where our school children shamelessly announce to welfare councillors that their goal for adulthood is to become pole-dancers. This is not the pornography of The Lost Girls.

Instead, Moore and Gebbie attempt to reclaim the notion of pornography, of mediated sex, from the filth peddlers and the scandal mongers. They make an attempt to recapture something of the spirited, wilful naiveté of various pasts, like some surreal collision of Edwardian smut (and it’s that complex, hypocritical Edwardian / late Victorian attitude to sex that itself fuels the middle class liberal guilt I feel – see Lee Jackson’s excellent novel The Last Pleasure Garden for more on this) and the wild bacchanalia of San Francisco’s free love of the late 1960s.

So yes, Lost Girls is about pornography; is about our responses to pornography and our programmed reactions to the mediation of sex. It’s also, inescapably, about the loss of innocence. Mainstream media, whilst gleefully mining the whole ‘coming of age’ genre, has always steadfastly refused to acknowledge the sexual element in any way other than that of suggestion or blustering teen bravado. Of course those approaches can give us some great moments, not least in the cinematic delights of, say, Fast Times at Ridgemont High or Some Kind of Wonderful, but what Moore and Gebbie are doing with The Lost Girls is (literally) putting flesh on those suggestions. And does that make The Lost Girls a more valid commentary on the nature of those times of sexual awakening than, say, Debbie Drechsler’s beautiful Summer Of Love? Of course it doesn’t. It’s not even a competition. It’s just that Moore and Gebbie are making the point that you can be explicit and charming in the same instant. They show that it’s not a simple choice between Tits and Ass or Merchant Ivory. That, at the risk of sounding glib, there is a third way: you can make stimulatingly graphic sexual acts graphically stimulating and yet retain the mystery and beauty inherent in the emotionally charged context. The Lost Girls is their sublime proof.

© 2006 Alistair Fitchett

(originally

published in the August 2006 issue of Plan

B magazine)