Postcards from the Lab

Marco Breuer’s Early Recordings (£35, Aperture) is the best photography book I’ve seen in a long, long time. Although conceptual in origin (Breuer’s processes include sanding, burning and rephotographing) these are beautiful, warm, involving abstract pictures, that really do push the whole concept of photography into new areas. At times mininimal, at times sparse, even ‘cool’, these pictures – or these reproductions of photographs – bear repeated and close scrutiny. Faint patterns and traces of colour and light emerge, new gestures and detail. The processes involved only add to the images, but aren’t the point of them: these are wonderful, engaging and engrossing photographs. I hope I will be able to see them for real before too long.

Matthew Monteith’s Czech Eden (£22, Aperture) contains less experimental photographs than Breuer’s, but is in an intriguing exploration of the Czech republic’s people and places. Think Martin Parr meets Peter Frazer and you will be in the right area: superb colour, and an eye for strange if not downright surreal imagery. Chairs seemingly holding their own religious service around an old stove, a tent inner strung up in a wood, a tram in the Prague snow, someone asleep beside their car in a small town. Graffiti, old warplanes, glass reflections, walls and cityscapes are in here, too, along with portraits whhose subjects stare back awkwardly at the camera. Elsewhere the natural and worn-out utalitarian meet and contrast; a naked man casually walks along the street, hands clasped around his genitals. The writer Ivan Klima provides an intriguing and thought-provoking introduction to this stunning volume.

Jacques Villeglé’s work involves the collection and collaging of weathered posters onto canvas, that is re-presenting found work within a art/gallery context. He has an eye for faded colour, awkward and humorous juxtaposition, for the beauty of tattered and torn edges, the seduction of patina and tear. This new monography (Flammarion Contemporary) contains a superb interview, an essay entitled ‘Poster Archaeology’, a useful and wittily entitled exposition, ‘Peeling Back the Layers of Time’, and a wonderful set of colour photographs documenting over 50 years of Villeglé’s art. There are many things beyond the obvious to consider: the re-use of popular and/or political images, the whole notion of appropriation, and the artist’s eye for exquisite colour organisation. This is a beautifully produced, long overdue, title.

In the same series is a monograph on Louise Bourgeois and her work. Whilst the book is as well written, produced and organised, I have the problem that I simply don’t find the artist’s work itself engaging. The author of the book, Marie-Laure Bernadac is chief curator at the Louvre, following many other important appointments in the art world, and her texts are lucid and informative; in fact, to my mind, far more interesting than the work under discussion. Bernadoc contextualises and critiques the artist’s lifelong achievements, providing a useful overview of themes and concepts throughout – namely the masculine/feminine divide, and the body & sexuality. Those who like Louise Bourgeois’ work will enjoy the book even more than I did, despite myself.

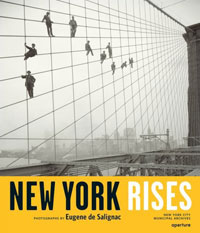

Meanwhile over in New York, Eugene de Salignac’s phographs of New York City under construction in the period 1906-1934, collected by the city’s Municipal Archives, have been published under the title New York Rises (£22, Aperture), along with two essays: one a biography, the other a contextual study, placing Salignac’s work in artistic and documentary perspective. Whatever there historical importance, these are wondeful black and white images of a world quickly receding into history rather than memory. Here is twentieth century industrial and architectural optimism, the new world of trams and cars, of new bridges and elevated subway lines. Here, too, are accidents and disasters as a result of these endeavours, here too is the depression and its effects: rows and rows of beds in makeshift dormitories, endless queues for the rumour of work.

Kirk Varnedoe’s work was, until 2001, as Chief Curator of Painting and Sculpture at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Pictures of Nothing. Abstract Art Since Pollock ($45, Princeton University Press) gathers up a series of lectures given the year the author died (2003). It explores answers to the question ‘what is abstract art good for’, as well as engaging with Varnedoe’s favourite artists & art, and also provides a history of the second half of the 20th century. I have to say I find it rather populist and easy reading, and not half as good as the publishers and blurbwriters claim. Maybe I am not the target audience, perhaps the book needs marketing (or is marketed to) to those who resist Modernist art and its fallout, but this is pretty much a bog-standard art history book with the usual suspects as examples, and the usual half-baked defensive appeals and statements for abstraction, as though form, colour and texture (etc.) don’t work the same in abstraction and pictorial/depictive art. It’s very disappointing, as is, I confess, Sean Scully’s Resistance and Persistence. Selected Writings (£19.95, Merrell), which I was looking forward to immensely, as I’m a huge Scully fan. I’m afraid I find many of the shorter statements collected here slight and inconsequential, and several other pieces I already own in magazines and catalogues. There is simply too much collected here, with repetition and digression the norm. It made me want to get back to the work, which Body of Light, a catalogue distributed in the Uk by Thames & Hudson, does admirably. Here are many quotes and excerpted writings, but with the focus remaining on Scully’s paintings, prints, drawings and photos. Here, too, is a new interview and some useful, if brief, essays by several writers including Arthur Danto.

Thames & Hudson also publish Francis Bacon. The Violence of the Real, which gathers up many of Bacon’s depictions of the human form. There is, in some ways, little “new” here, but Bacon’s work, perhaps more than many artists, is always intriguing when newly juxtaposed and arranged within an exhibition or catalogue/book. Here, the reproductions are placed alongside brief and useful commentaries, as well as several essays on the nature and notion of realism, portraiture, film and aesthetic ideas. This is a beautifully designed and important volume.

Finally, closer to home, I’d urge anyone interested in painting to get hold of a copy of Michael Calver’s Silent Moves, which is published by the Brewhouse Gallery in Taunton, Somerset, to accompnay an exhibition of paintings. Calver’s work explores the formal restraints of colour and pattern, often using bright colour to compress the sides yet leaving the top and bottom “open” – the painting seeming to project itself beyond the restraints of the canvas in the vertical plane. Despite their tight control and hard edges, these are warm and engaging, quizzical and considered paintings. The interview at the back of the catalogue intelligently debates process, technique, inspiration and artistic practise.

© 2007 Rupert Loydell